Apple Music's 100 Greatest--the Scruffs and Muffs

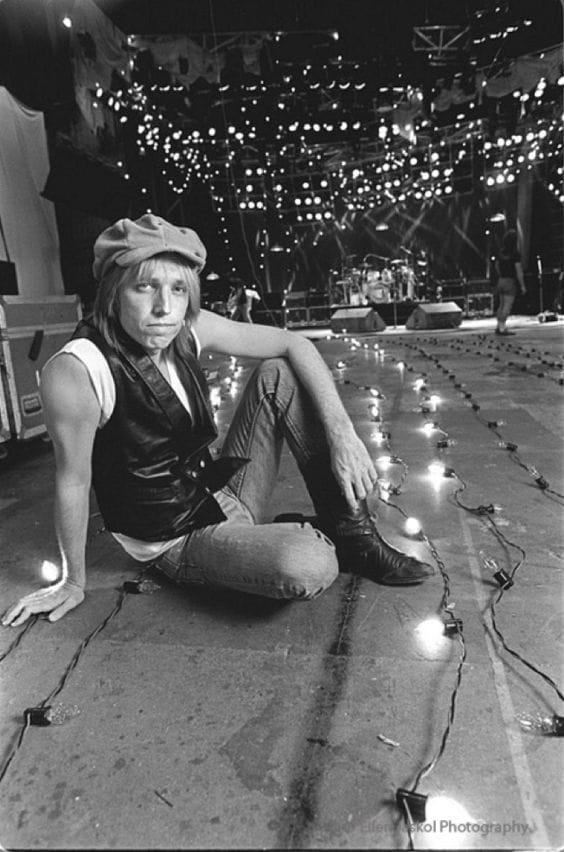

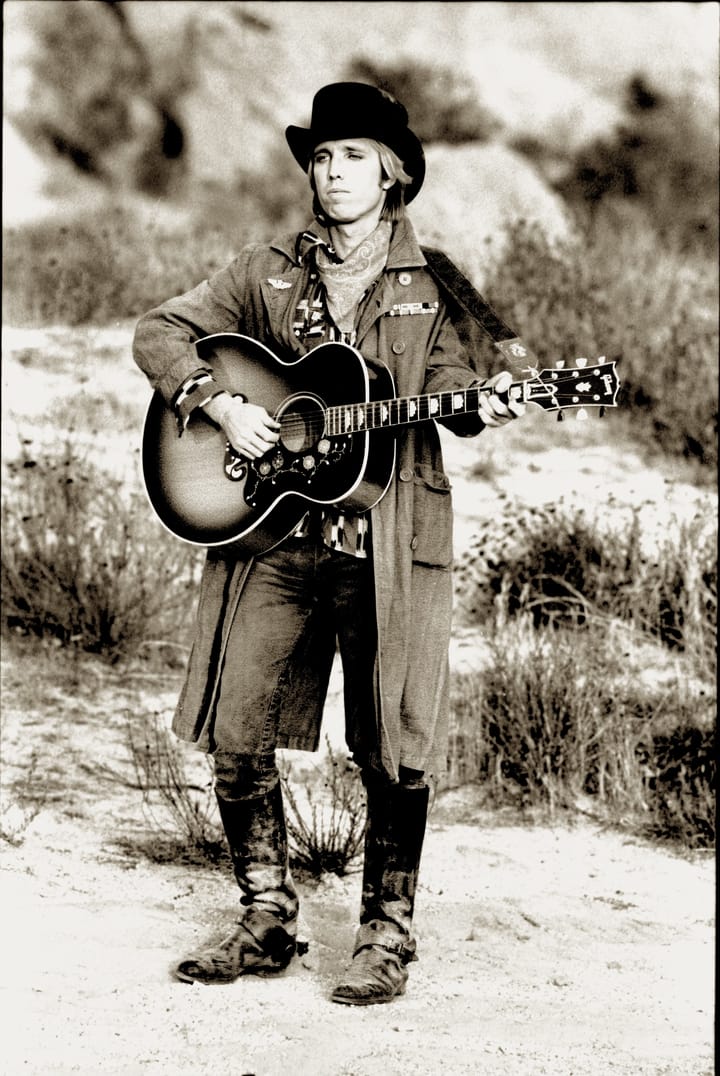

The incomparable Tom Petty is just one of the artists Apple Music's `100 Greatest' left in the wings

Was it about a decade ago that producers of written and curated content began to live by the tyrannical premise that a numbered list will quicken the pulse of consumers?

As a journalist working through various eras one noticed the rise of charticles, and only too soon, listicles. As editorial and various other media staffs shrank, the designated topic (“10 Great Rap Wars” and the like) could be compiled and spat into the ether by the inexperienced, sometimes even the ignorant, most of then harried and ill-paid, but still score page views.

I’m not crying, we’re all crying.

Despite our steadily lowering expectations for lists, Apple Music’s dropping of their annointing of the “100 Best Albums” stirred up considerable pushback, especially among the rock critics who wander the darkling plain of Facebook (where I’ll be posting this ASAP, as one does.)

The increasingly quaint pursuit of assessing shite tons of product (and indie-spawned, would-be product), which was once the job of self-styled elites (guilty as charged on the self--styled part), was being out-sourced to actual consumer-commentators. Should you drop a book on Amazon, better get your actual pals to cough up some several-star reviews before some shirty dude in Texarkana—the `r’ is doing a lot of work in `shirty’—moans online that the story you've written is making him titrate up on his meds.

We scribes were—are—ignorant enough about the actual creation of the music when covering it for pay was a feasible lifestyle choice; the remaining practitioners have seen their livelihood still further jeopardized by the expansion of an era in which everyone is a rock critic, including that guy next to you at the table reserved for the fifth most important wedding guests, a guy eager to tell you about the quondam wonders of every album from…please, no, really?--Air Supply? (I’m sorry, that’s your jam? Okay, just don’t start in on Chicago.)

A recent scientific poll of decent rigor helps establish why we shouldn’t be so aggravated at the vagaries caused by generational preferences:

YouGov polled more than 17,000 Americans about which period they believe had the best music. Among US adults overall, the 1970s and 1980s prove to be the best decades for music, with 21% and 22% of the vote, respectively. Slightly fewer point to the 1960s (14%) or the 1990s (14%) as standout music decades, while even fewer choose the 2000s (6%) or the 1950s or earlier (6%).

The other shoe of course drops in the fine print; put bluntly, we like the music we liked when we were coming of age.

The Apple Music tally’s almost farcical concentration on 90s albums surely reflects the age of the (rather murkily identified) deciders from Cupertino, and they were canny in making “The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill” a diabolically bulletproof choice.

Check the boxes: a hit album from a female person of color, one which to its great credit both summarized and set new prototypes for rap and hip-hop, and just happens to be the subject of a revival tour by her original band The Fugees, complete with Kimmel showcase—that’s a tall No. 1 for cynics to topple. (Rolling Stone, whose serial tallies of the Top 500 albums reflect an ever more diligently sourced array of musical artists, put Hill’s album —with its bitter near-homonym of “Miscegenation”--as their Number 10.)

Let’s get a little personal, for what is record-rating but that? Some of these works are simply undeniable. Prince as Apple’s No. 4 was RS’s No. 8, but then cracks appear: Apple’s “Rumours” by Fleetwood Mac was Rolling Stone’s No. 7, and Stone’s impeccable list-topper, Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Going On” was a mere 17th for Apple.

All seem to inarguable to this listener. But still more personal: Joni Mitchell’s “Blue,” No. 3 for RS, was No. 18 for Apple.

Not for the first time, I’ll cite George Bernard Shaw and his (okay, ethnocentric) comment arising from his side hustle as a music critic: "You have to like Mozart; it is a mark of caste."

Without “Blue” I’m not quite sure how I would have happily idled through the late afternoons of that album’s peak essentiality in the early 70s. I would return from driving a small truck full of weekly newspapers through the slushy Boston streets, and as dusk fell over slightly funky Brighton, share a “doobie” from a “lid” we bought from “furniture man” and then lounge about in strictly Platonic association with a friend’s girlfriend, waiting for him to get home from work while slugging a Pabst and listening to Joni sing--verily like a bird--on almost endless repeat.

Permit me the below restitiuion of a certain Apple-neglected personal favorite, Tom Petty’s “Southern Accents”.

This was the album Petty and Heartbreakers keyboardist Benmont Tench would cite as adversely affected by plentiful cocaine—witness that Petty would smash his left hand into a wall when he couldn’t find the right mix for the surging opening track “Rebels”—but there are ample reasons Rolling Stone acclaimed it the best of Petty albums on one of their lists of 500. ("Wildflowers" would claim top spot in 2023– no beef there.) The title track is among the most hauntingly beautiful of Petty songs, never more so than in the melodious bridge where the singer dreams of his mother--Petty had lost his own not long before--who "says a prayer for me".

Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers live in Gainesvulle, 2018:

It’s seems almost purposely obtuse of Apple to slight Petty. "Southern Accents" contains another monument. Having closed Side One with the emotive, quietly anthemic “The Best of Everything,” with its saluting horns:

She probably works in a restaurant

That’s what her mama did…

...Petty the spinner of cinematic scenes drills down into his plainspoken fluency, and gives lost love—or is it “never quite found”? love– a proper farewell:

And man we never had the real thing

But sometimes we used to kiss

Back then we didn’t understand

What we were caught up in…

The production owes much to Robbie Robertson, who set to work on the Petty track with the aim of using the song for Scorsese’s “King of Comedy” (Tom’s label later blocked that). Petty had handed the song off to Robbie with a promise to stay away until the Band veteran had completed his alchemy. With the addition of evocative horn charts like mourning bugle calls, Garth Hudson’s keyboards and Richard Manuel’s harmony vocals (as in, “Sometimes she used to sing…”), the song became imbued with a kind of loving regret for what once had been. It’s a “speak, memory” moment that inhabits both the relationship and the album's surrounding, distinctly Southern ethos.

In any event, the Petty exclusion will for other listeners sit alongside many other big misses by the Apple selection team. There will be time and space for grumblings over The Kinks, The Who, the under-representation of Aretha, the faceplant of ignoring Otis Redding…the list goes on. But perhaps the project's commercial aspect is already assured, and I'll give the list-makers this:, the past couple of days of listening to music as a reaction to their choices would have been the poorer had those supposed tastemakers not triggered us to dive into our own ideas of what stands as great music--recognized or otherwise.

Comments ()