David Lynch Was "A Designer, Builder, Artist" Says His Brother in Art Jack Fisk

The painful news of David Lynch’s passing this week brought forth a reaction from film people that was both reverential and slightly stunned. The community had known for some time that he was suffering from disabling emphysema, as he advised even as he cited hopes for the future: “I have now quit smoking for over two years. Recently I had many tests and the good news is that I am in excellent shape except for emphysema. I am filled with happiness, and I will never retire.”

The less promising news came with reports that the director had taken the cigarette habit back up, and as an added challenge, the Palisades fire had forced him to evacuate his Hollywood Hills lodgings and retreat to the home of his former wife and their daughter, out of the path of the hillside blazes.

The family confirmed his death on Facebook, writing, "It is with deep regret that we, his family, announce the passing of the man and the artist, David Lynch. We would appreciate some privacy at this time. There's a big hole in the world now that he's no longer with us. But, as he would say, ‘Keep your eye on the donut and not on the hole. It's a beautiful day with golden sunshine and blue skies all the way.’"

Perhaps too infirm in recent years to actively direct any new projects, Lynch did inscribe one more entry in the scrapbook great American directors with his cameo as a believably quirky John Ford in Steven Spielberg's s fictionalized film memoir "The Fabelmans": https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5mAyNNBOdns

For better or worse, Lynch’s last major project was an effort to revive his televised “Twin Peaks” saga (although its second iteration had somewhat diminished the property) with “Twin Peaks: The Return” in 2017. As David Ehrlich wrote in a Rolling Stone remembrance, “He dosed the nostalgia with even stronger, more lysergic narcotics. Its eighth episode, in which the root of modern evil is traced back to the Atomic Age’s big bang, remains one of the most harrowing things to ever air on premium cable.”

Ehrlich also illuminated some of the darkness underlying the director’s entire body of work with a reviewer’s assessment of “Blue Velvet: “It’s like Norman Rockwell meets Hieronymus Bosch,” and added an edifying quote from Lynch when he was asked about the film by Chris Rodley in the book-length interview in “Lynch on Lynch”: “This is the way America is to me. There is a very innocent, naive quality to life, and there’s a horror and a sickness as well. It’s everything.”

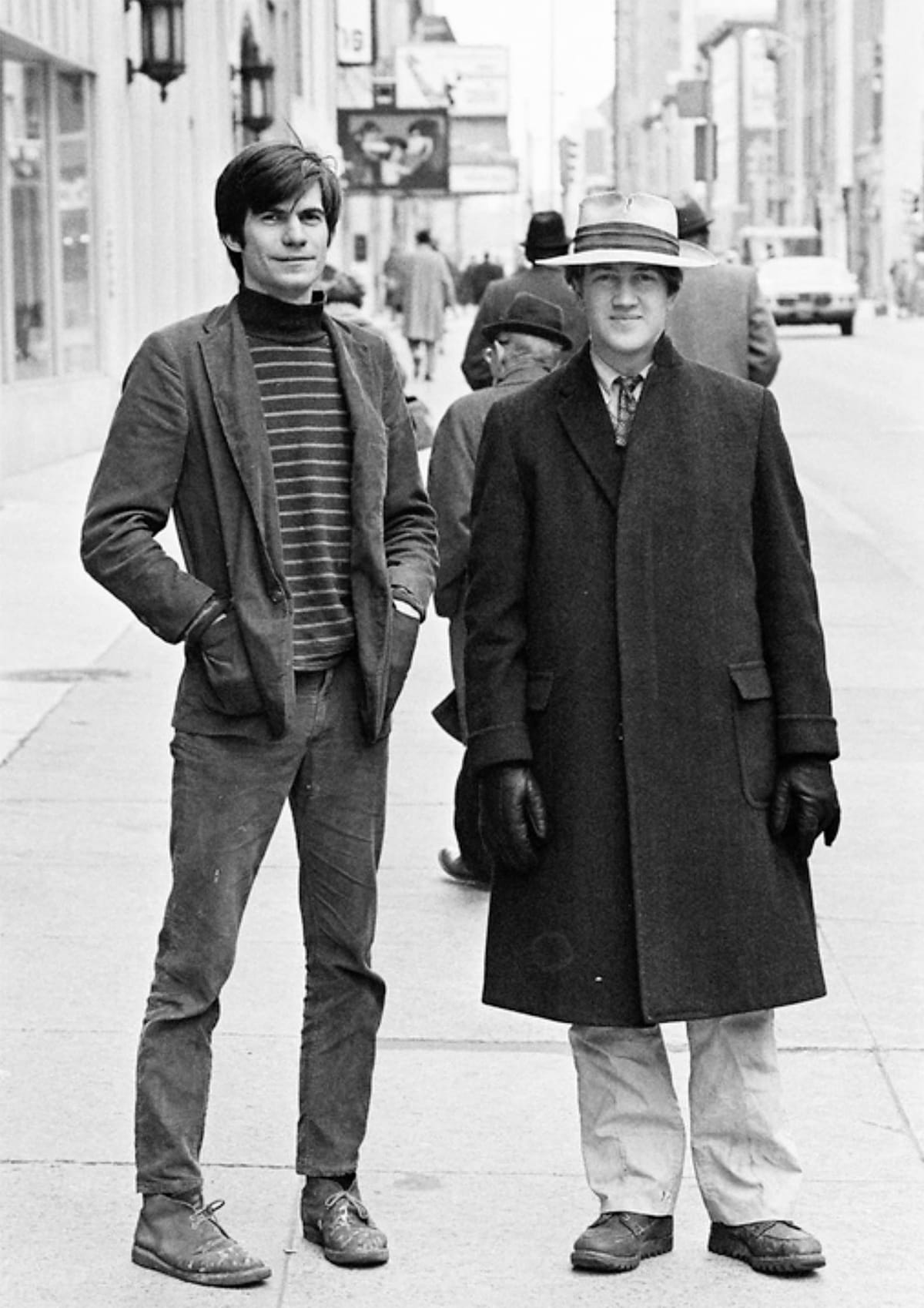

Around the time of the last gasp of the “Twin Peaks” iterations, I had interviewed his longtime best friend and key collaborator Jack Fisk for a would-be start-up magazine that had been planned around tribute coverage of Lynch. The magazine would be scuttled when the funding fell through, but Fisk’s insightful comments bear airing here.

Fisk, of course, despite a reliably unpretentious air, is manifestly a deep artist who readily inhabits the inspirations of some of our greatest auteurs. Oscar-nominated for his production design work on Paul Thomas Anderson’s 2008 “There Will Be Blood,” and Alejando Iñárritus’ 2016 “The Revenant,” then again most recently last year with Martin Scorsese’s “Killers of the Flower Moon,” he’s been equally celebrated for his work with Terence Malick.

Perhaps his most pathbreaking work was with Lynch, beginning with the precocious expertise and vivid talent he displayed on the director’s gob-smacking 1977 arrival film, “Eraserhead”; he added to near-legendary stature with the evocative milieu of 1999’s “Straight Story” and 2001’s “Mulholland Drive”.

If the latter film was an exploration of sometimes haunted, interior spaces and a kind of claustrophobic yet dreamlike world of a cruel Hollywood and its cold-hearted film industry, it’s no accident that we have come to associate many Fisk-designed productions with expansive spaces, from his earliest days. Witness the grassy, unrelenting plains of Malick’s 1973 “Badlands”(effectively his debut, on which he met wife Sissy Spacek), the wheat fields of Texas (crucially crowned by an old Victorian house that is a clear homage to his great inspiration Edward Hopper), and the ominous grassy hills ( mostly Australia standing in for Guadalcanal) in Malick’s 1998 "The Thin Red Line." And yet, Fisk smartly let nature speak more grandly via the prairie lands Richard Farnsworth rolls past in "The Straight Story."

“I love directors,” said Fisk unabashedly in our 2017 talk, “I think everybody would like to work with an artistic filmmaker, and I think Terry and David and Paul, and also Brian De Palma [for “Carrie”] and Alejandro Iñárritu--such passionate artists. That's where I feel most comfortable, is with creative people.”

One definitely senses that, in part because of the history they’ve shared in various locales and locations during key way stations of their career, that David Lynch is special, perhaps the first among equals.

“I built the house for “Carrie” based on the house that David Lynch lived in in Philadelphia—they used to call that [structure] Father, Son, and Holy Ghost. There were three rooms, one on top of the other, and then they'd usually have a bump out for a kitchen on the first floor. I just started building that. Brian just showed up and shot it. I kind of have this blessed life where it hasn't been complicated. It's hard work, but I seem to get along well with the people I work with.”

Asked about an archival photo of himself standing in front of the protagonist’s ramshackle cabin in “The Straight Story,” Fisk recalls the director taking a hand in prepping it. “David did a lot of the painting. The head painter and I put together a little paint kit for him and said, `Okay, David, you're in charge of standby painter,’ and said, "If you want something aged, you can age it." He just loved that. I don't know how often he got to use it, but David is a designer, builder, artist. He built all the sets for Eraserhead. It's fun to work with him because we talk the same language, so it's really easy. He also understands how long it takes to build something and he appreciates it when you can do tricks to make it cheaper or something. You can build stuff out of paper for him if it looks right and he knows it's fragile. He'll just shoot it. Everybody's happy.”

A longtime loyal art director across the recent decades of Fisk’s career has been Ruth DeJong, whom he met through his daughter and convinced to get into the trade. When approached by Lynch about the 2017 reboot of “Twin Peaks,” Fisk recalled, “David wanted me to do it, but I had just finished “The Revenant” and I was exhausted because I'd been out there for two years. I said, "You’ve got to get Ruth," because she and I worked close together for the last eight, nine years, and Ruth started working with him on it and they got along great. What I loved about the new “Twin Peaks” is that it looks just like his drawings. She did a beautiful job. She just got nominated for an Art Directors Guild award for that show.”

The impressive philosophical and creative heft of Lynch’s body of work, Fisk said, “Is probably coming from him meditating and being so spiritual that he thinks about all this stuff and all the different levels of reality and universe that are around us. I think it's expanding as his own consciousness is expanding, but he's always had kind of a little bit of a strange mind. I remember when we were in art school, we were at this little bar across the street from our house, and he was talking about his dream. It would be to, when he gets older just have a metal plate in his head and have all these women taking care of him, bringing him lunch and stuff. I was over at his studio a few years ago and he was sitting there and women were coming and bringing him coffee. I said, ‘You got everything but the metal plate in your head.’”

The gracious, reserved Fisk had some warm concluding words this week for his departed confrere. “I am savoring the effect David has had on my life – quietly,” he said, “I feel so fortunate to have had him as a best friend.”

Comments ()