"Ripley"'s Grain

If ever a show was a great fit for the West Side of L.A.—and I say this as a fellow denizen—it’s Steve Zaillian’s adaptation of the Patricia Highsmith crime classic, “The Talented Mr. Ripley,” re-billed "Ripley". It probably isn’t a good idea, even as the initial spate of enthusiasm modulates, to go to chow call at Craig’s without having at the ready a take on the show– along with Anthony Mighella's predecessor version--as it streams on Netflix.

Extra points on the West side for citing the Alain Delon version before appetizers, but more widely the show ranked first among most watched original series for the week of April 5, 2024, per the streaming tracker service Luminate, with 1.5 million views.

That said, I did hear an astute dodge from a friend just today: “I just moved places and I’m certainly not going to watch it on my laptop.”

That’s the rub: the wide appreciation the series has drawn is much thanks to its exquisite black and white cinematography, a fine-grained symphony of noirish grays, all of it derived from the art direction and assiduous location scouting, and taking its cadence from the many waiting-to-exhale single shots of the title character as played by Andrew Scott.

Zaillian wants us in Tom Ripley’s head as we watch him connive on the spot, even as he cogitates with seeming blankness on a solution to whatever new fix he has bludgeoned his way into.

This is probably the right moment to warn of mild spoilers ahead—but, and no judgment here, haven't we all had enough exposure to several variations of this saga to gain some familiarity as to key points?

The cleverness of the enterprise begins with the simple subtraction of Highsmith’s first three word for its original title; Zaillian has emphasized in interviews that in endeavoring to put the audience in the brains of an ad hoc killer, he wanted to show “It’s not easy for him—he’s not any better at it than we would be.”

The talent most on display in the eight-part series on Netflix is that of Scott (yes, the “hot priest” of “Fleabag”) who reveals an opportunist who’s measured, resourceful in a pinch, but a bit amateurish at the edges--depending on your view of ad libs like lip-locking with a fresh corpse. (Though Scott had a quick answerfor a interviewer who asked if he was Method actor—“That could be dangerous.”)

Part of Zaillian’s strategy, and he is deliberate visually and narratively almost to a fault, is to entrap us step by step in Ripley’s schemes. He taunts us to find the inner life of a man who has no obvious inner life beyond improvising ways to become a walking simulacrum of his first victim, Dickie Greenleaf, and the rich man’s lifestyle. (The prop master has a field day.)

The until-now better-known version is of course Anthony Minghella’s 1999 outing (the word applies doubly here) that spotlighted Matt Damon’s queasy and expertly fey turn opposite an intriguingly variegated performance by Jude Law as Dickie. With due respect to Gwyneth Paltrow as an emotionally battered Marge, Dakota Fanning’s strength in the new edition may surprise some. She is us, at some level, in her reserve and her suspicions--and her ambition.

Deglamorized but magnetic to the lens, mistress of an unnerving flat stare (Scott for his part gazes back with a tickle of vulnerability—“He’s just trying to survive,” he has said of Tom), she serves as our champion if only for staying upright. “The characters are saying one thing,” Fanning has observed, “but there’s so much more underneath, and the intention behind what they’re saying is sometimes the complete opposite of what is being said….to modulate a performance based on what’s not said…I was really excited by that.”

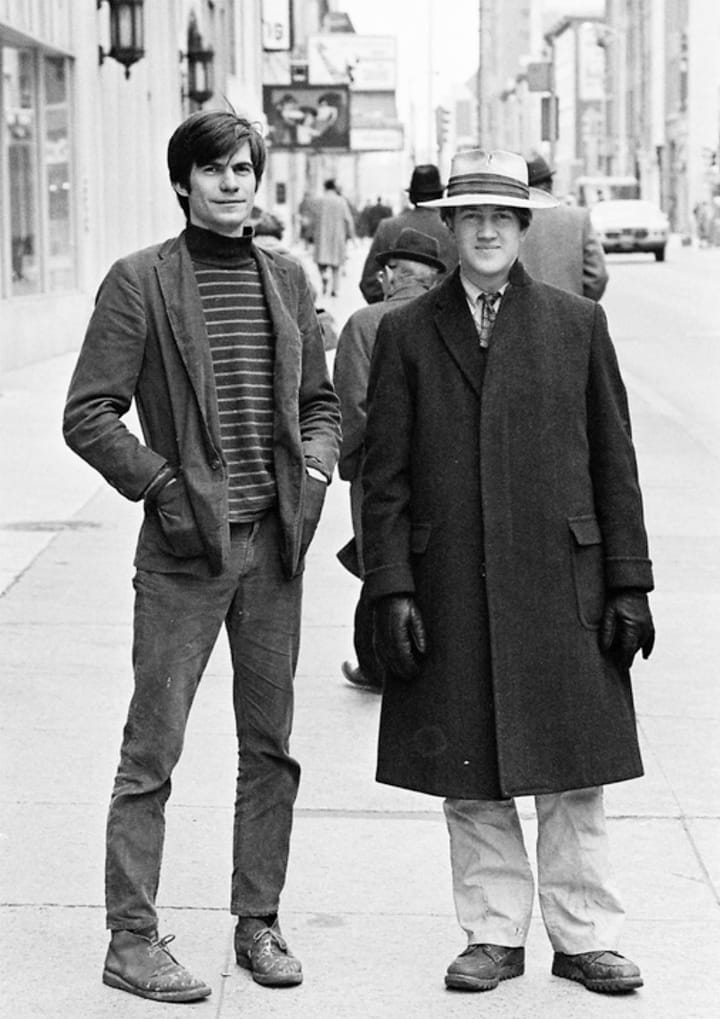

(To address the flaw many commenters have cited, there’s a certain photograph we notionally discover at the same moment as the show’s otherwise canny Inspector Ravini --a delicious Maurizio Lombardi; but even as the score's strings scurry teasingly along, many of us might only mutter a quiet “dang” at that, because we’ve come this far with so many storytelling and optical pleasures unfolding before us.

So alluring are the seaside vistas (held precisely at a length that lets us take them in almost as sandy Ansel Adams stills), the mournful or judgmental statues rising center-frame in the streets and steps (and more and more steps, and bloody stairsteps) of great Italian cities, that these coastal views also must be testified to in those dinner toasts.

It would be possible to write a long cinematographic paean to seasoned shooter (“There Will Be Blood”) Robert Elswit, and the state-of-the-art Arri Alexa LF he has deployed digitally on recent shoots after his years of great work sticking close to film stock. Zaillian’s rigor, but for one jot of read, fulfills its brief: in addition to a 1960 Rome (and Venice, and much more) that “wants to feel dark and dangerous “I wanted a grey ocean,” and of the entire project, the thought never presented itself to do it in color.”

Colorless too, and by design, is Scott’s performance. This show marks our full discovery of the Dubliner, 47, who scored raves in London as Hamlet, and when he performed eight roles from "Uncle Vanya" by himself, in a celebrated West End solo adaptation of the Chekhov play.

Scott has said that the arduous part of living in Tom’s head, through a long shoot dogged by pandemic protocols, was hewing to “the blankness.” He scuppers a bloody motorboat but never Zaillian’s firm vision, and we have only ourselves to judge if we take pleasure in Tom’s maneuvers—all the more so as one involving a toothily and toothsomely corrupt John Malkovich raises high hopes for a sequel.

“That’s why he fascinates so many,” concludes Scott. “There’s been so many iterations of [Ripley]. I think it’s because people root for him.

“I never thought of him as a sociopath or murderous. It’s up to everybody else to characterize him or call him whatever they want.”

Comments ()