Springsteen and "Nebraska": There's Been A Healing

Rochester, New York December 2, 1980, deep into The River Tour. It’s just minutes after The Boss has come offstage of the War Memorial Hall after a typically lengthy and committed show. He stands amidst his E Street bandmates just outside the stage door. The sidewalk is peopled with fans feeling lucky to greet their hero—a hang-loose, openhearted moment.

Ah, but in the freezing city a kind of white-gray frosting paints the sidewalk, rendering all those gathered almost hapless to walk even a step without sliding. It’s spreading and freezing still harder as one lad, with a bulky soft cast, has no option but to plant the injured limb gingerly on the stuff and slowly shuffle off, crutches borne in one hand. It’s comical to see, but Bruce—who’s a full service interviewee and feature subject—glances over at me with my usual tattered notebook out. “Look, Freddy!” he rasps, and it’s amazing that after four hours onstage he has an ounce of frolicsome energy still in him--“There’s been—a healing!”

In the Thom Zimmy-directed documentary “Road Diary” (Hulu and Disney), shot as the band ramped up for their summer European tour, we watch a kind of love letter to the E Street band and the entire Boss coterie, many of whom who chipped in with interviews and recollections after reuniting following a six-year gap. It tells its story largely through Bruce’s voice-over observations.

Thus the doc’s burden also is to show a different kind of healing, as a collective enterprise sets out to, as Springsteen says, “shake the cobwebs off” and “find the set list.”

It would shape up a mostly predetermined slate of 28 or so songs. In incorporating three albums of material the band had never played, the set list has upbeat moments to spare but goes deeper, taking on thoughts of what Bruce calls “the stakes you play for” as the aging ensemble and its leader confront “the burden of time and approaching death.” The man they call The Boss has made a point of stating he’ll never bill such a run as a farewell tour, keeping on until “the wheels fall off,” but there’s a hovering sense that no one can keep going with this fervor and energy forever.

That sense only increased the pressure on “dynamic” ticket prices, notriously to the alienation of even many lifelong fans. Seats for this tour hit a level of leisure-class aspirational right up there with say, an eighty-inch TV.

Even if you approached the film ready to be skeptical of what was being left aside, you only had to watch a few minutes’ worth to recapture the sense of the artist’s passion and lasting worth. However earnestly the various talking heads of band and handlers might lean into what some have seen as a messianic vibration, the principal’s mingled rigor and joy show a man devotedly doing his best to deliver for the fans.

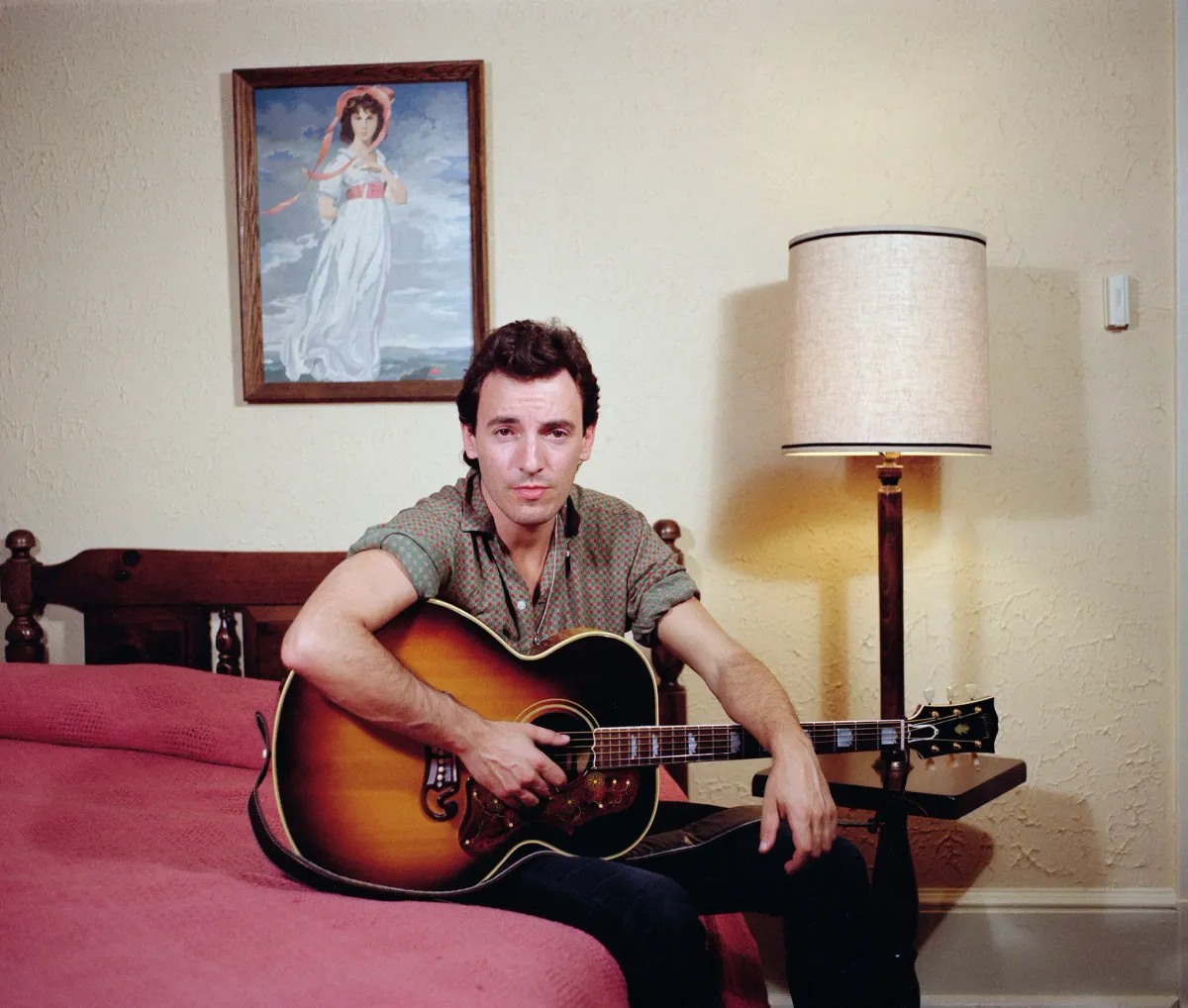

Largely to the side of that mission is the fandom’s current rediscovery of the “Nebraska” album, due in no small part to the book “Deliver Me From Nowhere” by gifted rock historian Warren Zanes. The book gives us a deep dive into the emotional crisis that led the storied songwriter to sit (mostly) alone in a room with an acoustic guitar and make a radically stripped-down collection of songs. Written with ample cooperation from Bruce—author and subject spent time in the very room in a humble Colts Neck, New Jersey house where the recording took place on January 3, 1982—it benefits from an array of interviews including the crucial insights of longtime manager Jon Landau. “If you listen to that vocal style on “Nebraska,” he tells Zanes, “It’s different from any other record. It’s like he’s singing to himself.”

Springsteen would tell Zanes the creative act was sparked by a genuine mental health crisis: “It was a strange moment I came off the River tour and I felt that hollowness…I was thirty-two, thirty-three, It was right before my first big crash, my depressive crash.” Part of the great worth of Zanes’s efforts is how he incorporates the story of Springsteen’s difficult youth and its impact into the wider discussions of his artistry. As he observes in one of the chapter closings that artfully reverberate, the story of a real-life monster was the way in: “In a murder spree somehow he saw his childhood.”

If the events that constitute the making of “Nebraska” aren’t notably cinematic at first read, Zanes’ framing of them was involving enough to entice wriiter-director Scott Cooper (“Crazy Heart”), who in turn recruited for the lead role the currently much cleberated Jeremy Alan White (“The Bear”).

The film’s burden (beyond comparisons to the much-hyped Dylan biopic that will drop first) will be in drawing the musician’s story out to show the depths of the personal dilemma, even as he exists as a paralytically alienated—even from himself—victim of loneliness. As he does on a couple of key occasions in his book, Zanes turns to primary and early Boss chronicler Dave Marsh, as quoted by Zanes: “Bruce was feeling suicidal…the guy in `Nebraska’ isn’t Charlie Starkweather. It’s him.”

There’s also palpable drama in the quiet desperation of taking the rough-hewn sounds of guitar and vocal on ordinary cassette tape to create a an album releasable to an avid public, as ad hoc mixing expert Chuck Plotkin began searching for the right maestro of knobs to bring the recording’s raw essence forth.

That’s where I stumbled into an obscure moment in the saga. It was 1982, at least a couple of months into now-despairing exertions by Bruce et al. to upgrade the tapes (at that stage on 2” reels, per Zanes’ account). I was flying from Newark—or LaGuardia?--—to Los Angeles on some sort of assignment for Rolling Stone. Sitting in my exit row seat where the airline divided we coach passengers from business class, I became aware of someone standing two feet away. It was Bruce, reliably wearing worn denims and white tee shirt.

A year before, I had filed a table-setting short feature for Rolling Stone from an early tour date in Cincinnati, where he was credited with erasing the heartsick vibes left from a December 1979 stampede that killed 11 concertgoers. I followed with a full-on cover story, wrapped in a classic cover shot and more inside by Annie Liebovitz. I’d joined the circus that tour—backstage and on the bus, so to speak, for 17 shows in ten cities.

For all of Springsteen’s generous access, the story only found its true center when I journeyed down to Philadelphia, the day after the day that should have seen the story ship to the printer, to see Bruce and band meet the shattering challenge of playing a show in the face of John Lennon’s killing the night before.

There are a number of classic Springsteen bootlegs, some authorized, that go back to 1978 and the tour that exploited the almost scary and certainly convincing depth of the “Darkness On the Edge of Town” songs. But “The River” as a touring agenda-setter brought equally inspiring fervor out of the great showman Springsteen is. “Of them all,” he tells Zanes of “The River,” it’s the record that most captures what happens when we play.”

In adapting the ethos of Hank Williams’ “Mansion On the Hill” for “Nebraska”, notes Zanes, Springsteen was “Planting a foot…in a more distant and decidedly southern past.” Similarly rooted was “Wreck On the Highway,” which found its title in a 1937 country song that became a standard in the hands of Roy Acuff and others. It was part of the ethos of “The River.” Zanes: "Both the album and tour were lasting statements about rock and roll. But that `Stolen Car' part of Springsteen, that personal part, was the heartbeat beneath the floorboards."

In Philadelphia that night, that unforgettable and to many who heard it, nigh-unmatchable performance was marked by a sequence of three songs that built a dire, compelling momentum. First came “Stolen Car,” with its stately piano, a prefiguring of the entire “Nebraska” moment; then "Wreck On the Highway,” which in other shows had marked the end of a brooding concert passage and is one of the singer/songwriter’s most searing entries in the voice of the common man, Bruce closing it with a plaintive guitar outro; and thirdly, “Point Blank," noirish and raw. It bore a spoken, rather than sung, narrative before the heroine—or as one could read into it, the so tragically deceased Lennon—was shot “right between the eyes”. Very strange noises, not the usual happy screams but almost disturbing peals of emotion, seemed to arise out of an audience undergoing catharsis. This being a Bruce Springsteen show of hills and valleys, the band would bust out with the joyously anthemic “Rendezvous” next.

Such was the prelude to our encounter on the airplane. Bruce wondered where I was headed, and I mentioned I’d be picking up a rental car and heading– as was he--to the default local rock `n roll lodgings, the Sunset Marquis hotel. With him was longtime No. 1 fan Obie, and Chuck Plotkin, the latter holding two cream-colored carboard boxes. That’s how a quartet ended up taking up all the room inside my tiny tin-can rental. Bruce rode shotgun, even as I nearly rear-ended a big Caddy in front of us, and had to shudder twenty yards along the road shoulder. My thought was, “I have seen rock and roll future,”—paraphrasing Landau’s famous declaration—“and I just damaged him in a low-speed car wreck.”

When they boarded the car, Chuck took good care to keep the cases securely on his lap. Bruce’s only response to what must have been my inquiring look was a shrug. “We’re gonna make some rounds,” he said, as a Mafia button man might.

This trip, to follow the narrative Plotkin shared with Zanes, was almost certainly the pilgrimage cited on the book’s page 194, to consult with expert mixer Steve Marcussen. (With whom they were able to etch the songs onto vinyl, but not quite to everyone’s satisfaction.) Of the conversation on that half-hour drive, one thing I recall is Bruce inquiring—we were in surf city after all—what my favorite Beach Boys song might be.

Oh, that’s easy, “Heroes and Villains”. Why, he wanted to know, asking casually but attentively. “Well,” I said to the man who was carting around the most stripped-down recording any major artist had tried offering to the public in recent times, “It’s got a little bit of everything—wild instrumentation, layered harmonies, sophisticated arrangements, and some really beautiful singing.”

“Yeah,” he said, with a throttled grin though hardly disagreeing, but perhaps pondering just how different his austerely spare effort would seem to his public.

There would be more turns in the road to get “Nebraska” to an audience, so surely I was not the last (feasibly) discouraging word. The rest is history, of course, and upon release, over time, as Zanes notes, “’Nebraska’ seemed to take up some of punk rock’s unfinished business, which was substantial.”

As Landau would tell Zanes, who does a good job in his middle chapers of documenting the veracity of this idea, “’Nebraska’ made the “Born In the USA” record possible."

And then the career indeed blew up. Springsteen had needed some convincing to feature “Hungry Heart” as the leading plank the two-record set that was “The River” into the marketplace. As Landau tells Zanes, “You can accidentally have a big hit. You can’t accidentally have a superstar career.”

“Songs, unlike people,” Zanes ultimately says in one of many insights worth quoting, “have remarkable patience as they wait for someone to hear what they are saying.” As it happened, the album would enter the top ten, but it’s being memorialized now for its gutsy artistry and its pivotal place in the Springsteen canon. “Its imperfections, its howls, its bent corners--none of it takes away from the power of the work,” says Zanes, “Quite the opposite.”

Just so. Near the book’s end, Zanes puts both the demand and the opportunity of the album that was like no other in the hands of the listener: “He trusted his art and he trusted us to do something with it.”

Comments ()