The Black Crowes' Attitude

Black Crowes 2024 Tour comes to the Greek Theatre in Los Angeles this summer.

Musician magazine, January 1993:

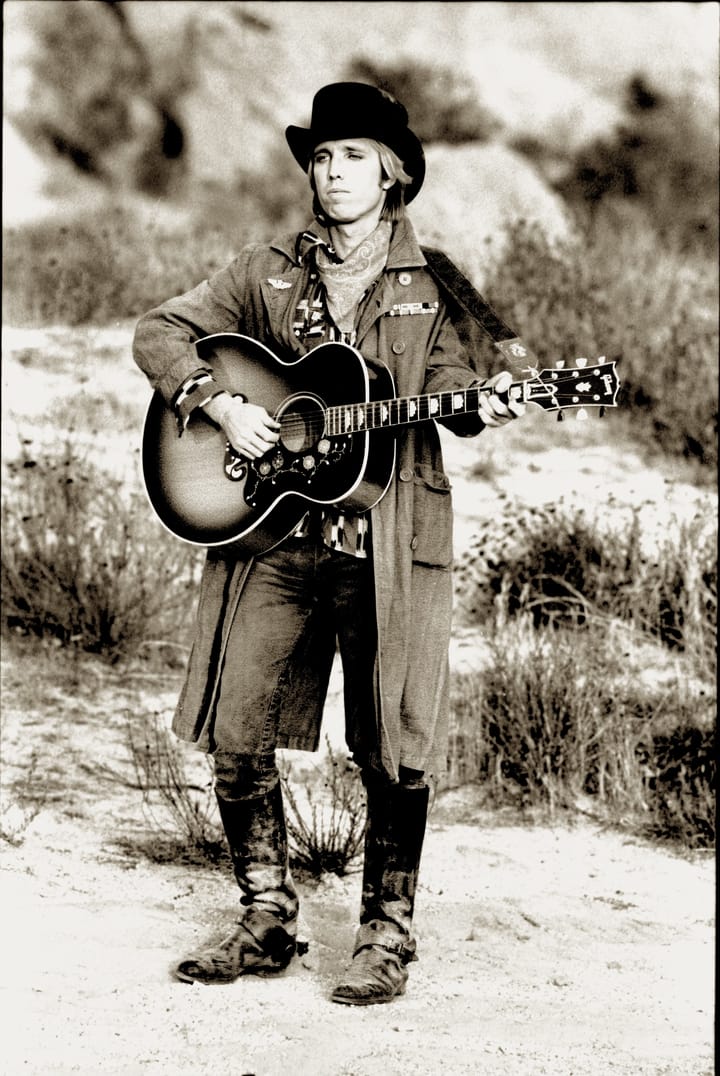

THE CORRECT ROCK 'N' ROLL ANSWER to society's "What are you rebelling against?" has always been Brando's "Whaddya got?" In this regard, Black Crowes frontman Chris Robinson does not disappoint, and it starts with his look.

Coming into view like a mobile made of metal coathangers, Robinson is a portrait of the charismatic street scruff you always prayed your sister wouldn't bring home. It's a defense. The guy who says hello from in there behind the wings of hair may be a Bad Boy, but he's not a bad guy. He just likes to tilt at big targets, and do it 24x7x365. They had attitude well before they were kicked off the ZZ Top tour for mocking corporate sponsorship.

"When we were on tour with Robert Plant," Robinson's saying once he's started his afternoon coffee in a New Orleans hotel bar, "his publicist said, 'You guys walk around here like you own this gig or something.'" His eyes do the crazy-world-ain't-it swirl that's second nature to him. "Well–we don't?"

It's the arrogance of selling many units fast. Every year, every month, almost every week, somebody goes Top 10 for the first time. It's often over the dread protestations of the critics. What makes the Black Crowes different is how well they have continued to sell, through two records, while watching their initially high critical esteem take a methodical beating.

"Well, it's just the weenie media like the local papers, so I don't give a shit," says Chris' brother Rich, who plays (rhythm) guitar and is the band's surrogate railer against the establishment. But when both the New York and Los Angeles Times diss you heavily ("Empty Nest" was the latter's headline), you've been slagged nationwide.

How did things get so contentious? It began with Shake Your Money Maker, their 1990 debut, and its rapid vault up the charts behind the Crowes' cover of Otis Redding's 'Hard to Handle'". Here was a creature in mirrored shades and a velvet jacket, Beatle boots and bell bottoms, long hair, spilling the song out in an auctioneer-quick Jawja accent. The band looked like good ol' (and I mean this in the best sense) rocker dopeheads. Chris had a mouth shaped like a cornet bell, an evident mixture of impulsive wrath and goofiness, and seemed to be put on earth for no good reason other than rocking. Mix in the song's sexual swagger, the duck-calling guitars and pushing-the-beat drum part, and the package was highly infectious.

To the Crowes' continuing consternation, even many positive reviews accused them of plundering from the Rolling Stones and Faces. The band has steadily insisted that what they shared with the Stones were not so much licks (despite Rich's open tunings, often compared to Keith Richards') as influences.

It would be churlish, therefore, to say that the first album's 'Tumblin' Di...,' er, 'Jealous Again' or 'Sister Morph...,' er, 'Sister Luck' sound Stones-derived. Is it the post-Exile cover art that makes one wonder if the second album's 'Bit...,' ummm, 'Hotel Illness' evokes the Glimmer Twins? They've also been accused not of using drugs, now a pro forma marketing ploy thanks to the Keef-et-al legend, but of "junkie-chic" posing. "Oh good heavens, baby where's my medicine," sings Robinson on 'Hotel Illness,' "... the scars I hide are now your business..."

Robinson pleads otherwise. "I have a really hard time talking about lyrics," he says. "I don't write narrative music as such. But 'Hotel Illness' to me sort of prefigured the L.A. riots. The entire song is being in Europe and seeing the United States from there."

Seen that way, "I got a head full of sermons and a mouth full of spiders/The politics of the world's greatest liar" does click as being "totally satirical. How many DJs across the country sit down and say, 'Well, I guess they're tired of living in hotels.' Well, we all live inside a big, huge hotel, man–I mean, where the fuck are you going? Everything's being taken so literally..."

Derivative or no, Shake Your Money Maker won a massive vote not only from consumers, but from several critics' polls. And not for nothing. On 'Seeing Things for the First Time' the brothers wrote a song Chris could sing the bejesus out of. By the time he sings, "You won't find me down on my knees.../Won't find me over backwards baby, just to please..." for the second time in the song, he's all het up. The keening vibrato he brings to "knees" and "please" is almost Mahalia Jackson territory, and it takes nothing away from Jagger or Stewart to say that they couldn't carry Robinson's jock in that passage. By the time he wails to the song's end, you may be inclined to forgive Robinson much of his complaining.

By the same token, it only takes one listen to 'She Talks to Angels' to understand Chris' protest that there's a lot more Steve Marriott in his style than others mentioned more often. Throw in Paul Rodgers and smear liberally with Aerosmith and you have his white-rock underpinnings.

Chris Robinson is but 25, Rich two years younger, but they grew up in the suburban Buckhead section of Atlanta fully convinced that they'd form a band. Dad Stan had been a folkie, an actor, and even had a couple of rockabilly-style novelty hits. Chris was the musical omnivore, indoctrinating Rich with everything from '20s jazz to Television, while Rich went for Dylan and the Byrds, and especially the picking of Clarence White. He got into open tunings not solely thanks to Richards ("Who gives a shit for Keith? How about Robert Johnson, Ry Cooder, Nick Drake?"), and despite occasional solo forays, basically fills the role of Chris' liner notes: "Very loud in the left speaker." Guitarist Marc Ford ("most of the bits called the solo") replaced original member Jeff Cease, who Chris says refused to improve with his bandmates. The Crowes still curse Cease's attitude. Asked if Cease could have honed his chops, Chris says, "I don't know–could the South have done better at Gettysburg if we had M-16s?"

The second album seemed to suffer not at all from the brief time they lent it – a couple weeks finishing off songs begun on the road, and only eight days in the studio. Chris says he sequenced The Southern Harmony and Musical Companion like an old, flip-it-over vinyl LP. His best segue may be going from the Stonesy (there we go again) opening kick of 'Sting Me' straight into its close cousin 'Remedy'. After that a certain turgor locks in, and there's chilly defiance in making Bob Marley's 'Time Will Tell' the closer. Luckily, the album plays like a suite, with the well-crafted if disconnected lyrics popping up compellingly throughout. They didn't succumb to sophomore jinx. But it may be that the third album will be the one that shows if they've got the long-term stuff to back up their gumption.

The band doesn't doubt it for a second. They've forsaken virtually all local interviews that bands usually use to sell tickets and win friends on the road. Luckily, they're playing compact 4000-seat halls that sell out readily for them.

For every protest they make that they're against image-mongering, they've been waging a tedious, many would say bogus, war with the local security. If you arrived the minute they lit into their first number, you weren't likely to find your orchestra seat. New Orleans audiences tend to need seducing, but the Crowes fans were thick and boisterous at stagefront. Robinson wanted them there – all night –and he made that clear. "Hey, leave them fucking people alone, man," he hollered into his mike. "You people don't understand that everybody paid good money to come have a good time."

That's phraseology that, in a campaign year, is readily recogniz¬able as rhetoric. He made this scene in virtually every city. Large sections of their set amounted to sludgy jamming that would have been hooted off the old Fillmore East stage. But as they slammed into 'Hotel Illness', they ascended – even through the ritualized unveiling of the pro-pot banner to Marley's 'Three Little Birds'" and the later display of top-hatted Leon Russell's picture during 'Remedy'. Chris whirled about on the band's travelling Oriental rugs.

By the show's end, fog machines and spotlights had created a, well, purple haze, and the band and most of the now-untrammelled throng were conducting a love fest. "You step out there every night," Chris had said over coffee, "and may not know the difference between Memphis and New Orleans while you're onstage. But at least that's your Shangri-la. And you can take Shangri-la anywhere you need to go." Retro or no, that's a definition of rock 'n' roll the Black Crowes are doing their damnedest to live up to.

Comments ()