The “Cultural Tragedy” of the Suppressed Prince Doc

The words in quotes in the above headline for this post come from New York Times Magazine culture editor Sasha Weiss, as spoken in a podcast cited below. And she’s right, of course—she steadily proves that throughout her exemplary, 9,000+-words article on the topic (“The Prince We Never Knew”)—but we also know what the deeper tragedy is. That would be the magical pop star’s death on April 21, 2016, at age 57, of a fentanyl overdose, alone in an elevator at his Paisley Park retreat.

His death is not quite as hard to plumb as the life he lived, in a career and a personal saga in which mysteries encircle mysteries. But before getting too somber, I will share a close-up Prince encounter in which he certainly had me mystified.

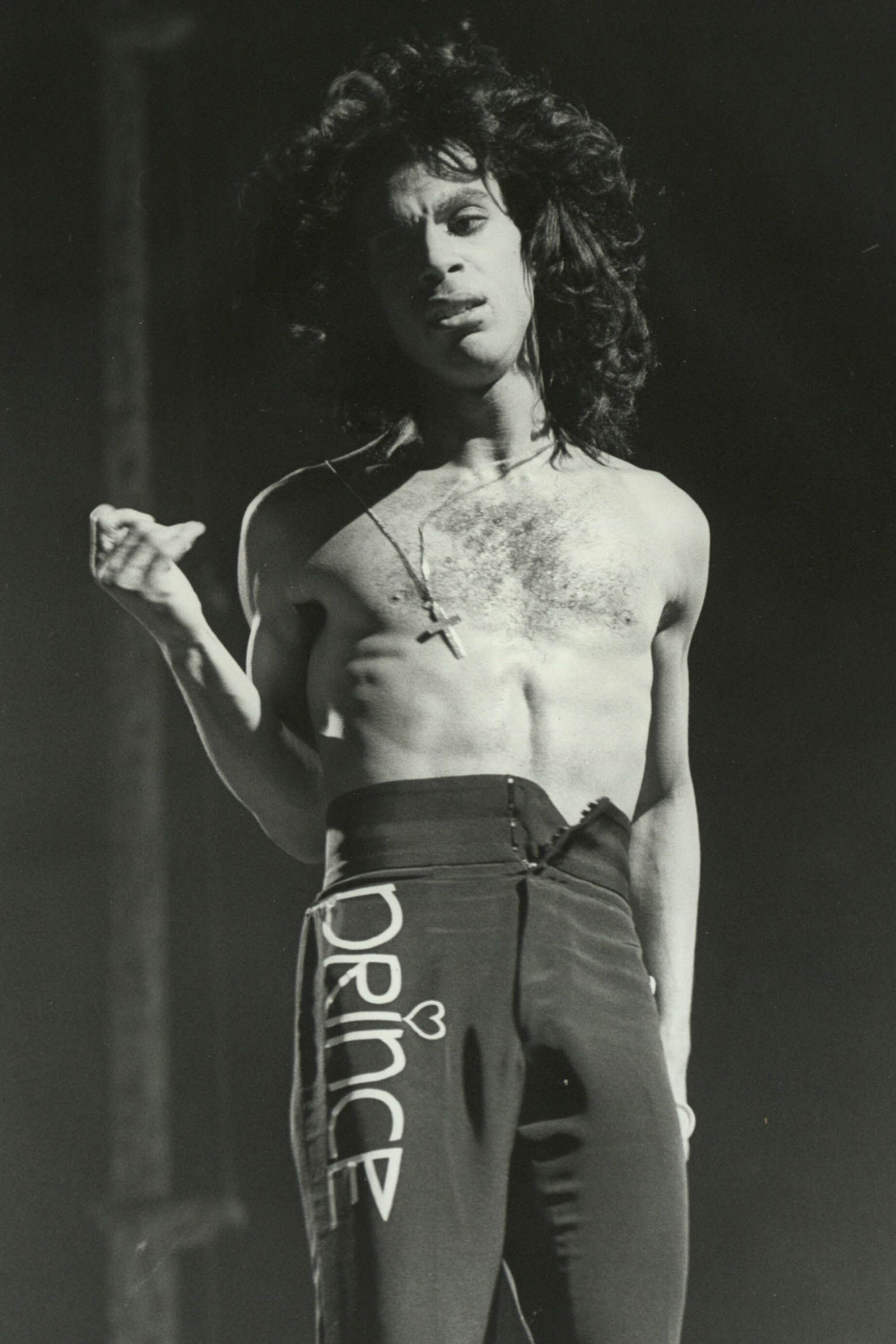

The first time I laid eyes on the man, he was shirtless, standing two feet away. It was April, 1978, in the Manhattan disco Xenon.

Xenon was Studio 54’s less fabulous, nascent competitor. If Studio was gayer, more Hamptons-y, more Warhol, and harder to enter, Xenon was more record-biz, more bridge-and-tunnel bougie.

Celebrities still abounded, and they, like the civilians dancing there, seemed to wear fewer clothes than the Studio crowd. I didn’t know at the time that shirtless was simply how Prince rolled then. (Or know who he even might be.) His first Warners Brothers album, “For You,” had just been released. The “Soft and Wet” single—the start of all of us going, “Oh now I get it”, wouldn’t drop until June, with some mild R&B chart success.

What happened that evening was, in the naturally unnatural way such things happened in those days, would be that your boy here (me), as newly installed correspondent for the Random Notes section of Rolling Stone, would as a matter of course be introduced to a new artist on the label. Gary Kenton, a chipper, eager, company publicist, did the honors after I sidled up to say hello to him without actually being curious about the charismatic 5’2” elf in tight (and spangly, I seem to recall) toreador pants. “Fred?—“ he said with a touch of ceremony—"This is—The Prince.”

There was a beat. The Prince, as I would continue presuming his show biz moniker to be, offered a handshake that was as low in affect as his brief, half-interested glance towards me.

A certain magnetism shone through, you may be certain. And although Gary vouchsafed over the disco thump that The Prince had a debut album coming out shortly on Warner Brothers, and I knew the label generally had solid signings, the incuriosity of The Prince about me was nearly matched with my own—shame on me!—about him.

Of course, we know much of the rest, so many details, and so many exhilarating public moments in a career that resounds with both musical genius and something darker. The murky part is imbued with the sort of still-reverberating regret that hangs around when a major figure’s fame meets up with poor lifestyle choices.

Per the headline, the actual burden of this post is to point to and applaud the work of Ms. Weiss, who in her September 8 magazine article on a “cursed masterpiece” gives the best account we are likely to get of what should have been a momentous, legend-defining documentary about Prince Rogers Nelson. He' s known to multiple generations as a son of Minnesota—and to much of his once-wide fan base as the son of a controlling , obstreperous father who gifted him, if that is the word, with his name. The documentary in question sits unreleased in the Brooklyn coffers of its director, Ezra Edelman (and intended streamer Netflix) who won a best documentary Oscar for his nearly eight-hour, 2016 HBO doc “O.J.: Made In America.”

Weiss, the culture editor of the Times magazine, was among the few shown the nine hours of Edelman’s Prince film, as it now awaits a seemingly unlikely sign-off from certain managers of the Prince estate who have put up legal roadblocks.

“Over a year and a half, “writes Weiss, “I had observed as Edelman continued to perfect his film, working to capture the essence of Prince, even as it became slowly, painfully clear that it would most likely never air. The Prince estate had changed hands, and the new executors objected to the project.”

Weiss cites sources detailing the tens of millions of dollars Netflix had paid the estate to secure exclusive access to Prince’s personal archive, referred to among Prince savants as “the vault.” And yet, she adds, the filmmakers found “there was almost nothing that was spontaneous or personal in the vault, almost no footage of him recording or writing.”

Three of Prince’s heirs have reportedly not raised objections, but the blockage arose from a second group made up of the other three heirs and L. Londell McMillan, a lawyer who worked with Prince in the 1990s and 2000s, and Charles Spicer, a music producer.

There is no question that Weiss, in reporting the story, reached a feeling of active animus against the lawyer and heirs she views as chiefly interested in maintaining Prince’s legacy as clean enough to help sell any remaining marketable enterprises to a still-eager public: “[McMillan] is also a polarizing figure whom several people characterized to me as controlling and bullying . Jay -Z famously went after him on his album “4:44”: “I sat down with Prince, eye to eye/He told me his wishes before he died/Now, Londell McMillan, he must be colorblind/They only see green from them purple eyes.’”

As an example of the sort of concert footage that may never be seen in full context, she notes that “Edelman presents the story behind Prince’s famous guitar solo during “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” on the night he was inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 2004. One video of the performance promoted by the Hall of Fame has been viewed more than 29 million times on YouTube.” Weiss adds: “A close friend of his later told me that Prince would watch this performance over and over.” (Her story makes no mention of the moment—here’s more mystery—when Prince heaves his guitar into the air overhead, and it bafflingly disappears from view.)

Crucial to Edelman’s process, and requiring four years to bring in for interviews, were the storied bandmates-and love partners to each other-Wendy and Lisa, whom Prince had relied upon for both music and sexy, side-eyed affect as members of his primal Revolution band. Eventually the religiosity he clung to in aler career stages meant he asked them to denounce their homosexuality when he wanted to reform the group. Their input, Weiss notes, meant Edelman was relieved to feel “He had found the emotional core of the film.” Weiss, who steps out of reporting mode to offer occasional pointed observations on the man who once tried to masquerade as a mere symbol, offers that “This creature of pure sex and mischief and silky ambiguity, I now saw, was also dark, vindictive and sad. This artist who liberated so many could be pathologically controlled and controlling." And: "I had always taken Prince’s yelps and cries as transgressive, in-your-face sexuality; watching the film, I understood that they also carried real grief.”

Or as Wendy told Edelman, “When “he’s screaming, there is a look in his eyes of pure torture.”

Previously unknown, yet deep, insights steadily arrive. Prince’s parents broke up their tumultuous, even violent union when Prince was 6 or 7, and his mother remarried a man who locked Prince in his bedroom and handed food to him almost prison-style. When Prince emerged, the sources said, he was emotionally stultified: “He went inside.” When reuniting with his birth dad went bad and the youth was kicked out of his house at 14, “It broke his heart, “ Prince’s sister Tyka told Edelman.

The cadre of Times colleagues Weiss often gathers for insightful round tables on the magazine’s site, including critic Wesley Morris, are consulted at points, but the charged insights and thoughtfulness Weiss brings are clearly her own and make one wish that she stepped away from her editor’s desk more often to compose solo efforts of the sort she wrote about personal exemplar Janet Malcom. In a consideration of that landmark, steely but sensitized journo’s career: “This is a signature tension in Malcolm’s work. She is luxuriously attentive but also ruthless in articulating what she sees. In one motion, she honors and critiques.”

Weiss’s piece smoothly mixes in insights on the inner Prince that carry both threads—in phrases she uses for Malcolm, “loving disapproval” and “helpless empathy”: “This creature of pure sex and mischief and silky ambiguity, I now saw, was also dark, vindictive and sad. This artist who liberated so many could be pathologically controlled and controlling.” Across the sprawling but always flowing piece, she embodies what she finds in Malcom’s work.

In her absorbing dialog with Matt Belloni of The Ringer for a podcast titled, “The War Over the Secret Nine-Hour Prince Documentary,” she and Belloni lean into the contrast between Edelman’s stern filmmaking motivations and what else passes for documentary these days. They agree on her written take that the medium (and especially Netflix) has in recent years “moved away from the kind of prestigious, provocative films that helped make the company’s reputation, toward content that is inexpensive to make and appeals to a global audience.” Overall, Weiss says in her piece, the streamers and networks now lean into presenting “Gauzy, entertaining celebrity documentaries — of, for example, Beyoncé, David Beckham, Taylor Swift, Jennifer Lopez, all of whom were intimately involved in their creation.”

Both Weiss and Belloni credit Netflix with resisting McMillan (who “sees dollars,” according to Belloni) and the estate’s attempt to cut Edelman’s nine hours into six, with multiple bowdlerizing changes. They cite as contrast HBO’s legal squabbles in defending the pull-no-punches Michael Jackson doc, “Leaving Neverland.”

The duo even suggests that if McMillan could be pressured into slaking the corporate fear of adverse “generational impact” on the Prince legacy, if he'd realize a new, younger audience could discover him through the film—possibly a win in commerce if not reputation.

Weiss’ summarizing thoughts take me back to that late-70s moment in a Manhattan disco, when a guy who for that moment was The Prince to me was merely potential energy, a near-unknown: “Edelman’s film restores to Prince some of the things he could never achieve for himself. It’s an act of witness and a kind of accompaniment for a lonely musical genius. But through some grim cosmic poetry, it, too, remains locked in the vault.”

Her ultimate take would be quite recognizable to Janet Malcom: “I thought about whether seeing these images amounted to a desecration. Does the whole world need to know about the very private, ugly torments of this genius? But then I registered the dominant sensation the film produced, which was awe.”

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Weiss article in the Times:

And on The Ringer podcast with Matt Belloni”

https://www.theringer.com/2024/9/20/24250382/the-war-over-the-secret-nine-hour-prince-documentary

Comments ()