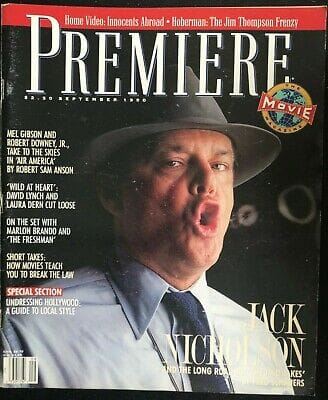

The Would-Be Classic That Ripped A Hollywood Friendship Apart

From Premiere Magazine, September 1990:

"As star and director of ‘The Two Jakes,’ Jack Nicholson worked unstintingly to get the movie made. He won the battle - but did he lose Robert Towne as a friend?"

In July of 1989, I found myself on the set of "The Two Jakes" even as the creative and brotherly cracks opened between director/star Jack Nicholson and screenwriter Robert Towne. (The latter died July 1, and is subject of my IndieWire obituary, found above on this site.) The following are excerpts from my Jack Nicholson cover story that came out timed to release in August, 1990--F.S.

OJAI, CALIFORNIA, is a verdant spot that nestles against the San Rafael Mountains, 50 miles north of Los Angeles and well-sheltered from the desert, but “Hot as a bastard, ain’t it?” is the obligatory late-morning question among the crew of The Two Jakes as they labor to prepare a shot for the film’s director and star, Jack Nicholson. Today - July 12, 1989 - is listed on the call sheet as the 58th out of 65 shooting days. The day’s work is on the lush grounds of the Ojai Valley Inn and Country Club. On paper, things with the production are still as they say, jake - “on schedule and on budget” will be the gist of Nicholson’s terse postscript to his work eleven months later—but the unhappiness surrounding this show has been deep and persistent...

But Chinatown, in its conspicuous greatness, has dogged The Two Jakes from the beginning. The years that encompassed the follow-up’s tangled history tore gaps in the relationships among three close friends - Nicholson, producer Robert Evans, and screenwriter Robert Towne - who launched the film Polanski so magisterially directed. A 1985 attempt to film The Two Jakes, with Towne directing, collapsed when Evans, who was to play Jake Berman, refused to relinquish the role on the day shooting was set to start. The settlement of the legal and fiscal squabbles emanating from that fiasco is sealed, and the parties involved are bound by signatures in Paramount Pictures dossiers not to discuss it or the further machinations that made the project’s phoenixlike rebirth last year possible.

... Towne says he aimed the sequel to expand on Chinatown’s theme of “the futility of good intentions,” with World War II “kind of obliterating that preexisting feeling for Gittes, counterbalancing the despair It had been a war worth fighting, worth winning, and he had acquitted himself well [the script establishes that Gittes won the Navy Cross]. The world would be a better place, he’s a little fatter and sassier – his insatiable curiosity is not the only thing by which he lives.”

...If Nicholson was born to play Jake Gittes, Towne was raised to write his story. Bom in 1934 to a family in the real estate business in San Pedro, Towne had watched Los Angeles boom in the postwar years What’s more, he knew its history, all the way back to the Owen’s Valley water scandal in the early decades of this century, which supplied the basis for the script’s scandal. Towne wanted to write a sensual and sentimental history of a Los Angeles that held a Proustian richness for his somewhat feverish imagination “Chinatown for me,” he would write, “was an acknowledgment that I lived with things I loved but could no longer see.”

“Roman and I were in fundamental agreement that Chinatown involved that futility of good intentions.” says Towne. “But [we] had a basic disagreement where at the end he wanted her killed and the father to get off. I felt that was too nakedly melodramatic—too much of a tunnel at the end of the light. I said, ‘Okay, Roman. I’ll do it your way, and you’ll hate it.’ I wrote it, and he said, ‘Bob, it’s perfect.’”

...As recently as the 1982 publication of his script, Towne cited in the preface his “enduring disappointment over the literal and ghoulishly bleak climax.” Today, a couple of years after working intensively with Polanski as a script doctor on Frantic, Towne admits that with the difficulty of cinematically capturing the “novelistic” ambiguities of his original ending, “I’m not so sure Roman’s isn’t the best way to do it.”

...If Evans today seems to carry a threadbare elegance, the same could be said for the damaged relationship between Towne and Nicholson. It was strong enough to withstand the collapse of the project in 1985, strong enough for Towne to submit a revised shooting script that was approved by Nicholson (and Paramount) in late ‘88. But during the rewrites of ‘89, their partnership frayed and broke. Somewhere between the plot intricacies of Towne’s script and the poetic imagery Nicholson wanted to wring from it, the two were simply not understanding each other any longer.

"Yes." says Towne, angry at the innuendos from various sources close to Nicholson, “there’s been a level of estrangement from the project, from me and Jack, that is undeniable and silly for anybody to deny."

...Towne won’t explicitly place where he and Nicholson lost communication, but he sneaks in general of how gaps grow: “Those people that I knew ... we started as friends, came together to work together. And as the years go by, subsequent professional entanglements with people other than ourselves start pulling us apart. You think you know your old friends: you read about them everywhere, they’re public figures. And they’re your close friend, and pretty soon you realize you haven’t spent more than a few days every six months with that person … but you perhaps have a feeling of false intimacy, as a fact that we’re exposed indirectly to our friends in the same way the public is.”

...The rift in the Towne-Nicholson friendship has hardly been lessened by quotations in Los Angeles magazine from producer Harold Schneider, who claimed Towne was completely unnerved - “in a fetal position under the couch’’- at the prospect of shooting the 1985 version of The Two Jakes, Towne denies the depiction. There were further quotes from a Nicholson intimate on the production in July 1989: “(Towne) has been disappointing to us. Let’s just say that maybe sometimes it’s like he didn’t want the job to succeed. You can say that Jack has suffered. This has been a movie of lost relationships for him on the personal side.”

...As far as Jack and I are concerned,” ripostes Towne, “I can only say that I did the best I could.” To charges that his eventual absence hurt the film, “my response is, ‘Why are people saying it?’” He asks if there have been any press screenings of the picture that wrapped principal photography in October 1989 - a picture originally scheduled to open in Christmas of that year, then March 1990, and finally August. “I mean, why don’t they just let you look at the movie and decide on that? If the movie is good, no amount of discussion of my shortcomings is going to hurt it, and if the movie is bad, no amount of that is going to help it.”

...As a guide for playing the drunken, lunatic, but sporadically elegant Lillian Bodine, Madeleine Stowe says, “Jack told me, ‘Don’t worry about going over the top.’” She found inspiration in Nicholson’s “very kinetic, jagged, fire-crackery energy. The picture very much has that, so it’s not fluid like Polanski, but it has its own particular life.”

“This movie is so densely packed with information and character relationships,” says Nicholson, “that the clues have to be there. You don’t have time, like they do in most movies today, to play two or three rock ‘n’ roll songs and that’s meant to tell the story of the picture.

“Because of Robert’s influence,” he continues, “it’s a very literary piece. No car chases, no dead innocent bystanders while I’m supposed to worry if they catch the Russian dope addict - I hate those movies.”

THE TOPIC OF A THIRD PANEL TO THE TRIPTYCH is greeted almost mournfully by both Nicholson and Towne, and they’ve diverged on its precept as well. Nicholson has always said that the first picture having begun in the year of his birth, the third one would take place in 1959 - “the year Robert Towne and I met in L.A.” For Towne, the answer now is more prosaic, having to do with Gittes’s bread-and-butter work as a matrimonial snoop. Yes, Towne allows, the third panel would take place “in 1959. Do you know why? It’s the year that no-fault divorce came to California.” He makes it clear that he’s not working on that script anytime soon, though he says there’s a start on it somewhere - “Yeah, there is - I would have to dig it out I haven’t looked at it.”

...Amid Nicholson’s considerable tact, hidden beneath his formidable defenses, one senses a kind of discomfiture with his world as it’s presently constituted.

It’s the kind of malaise Robert Towne is a qualified expert on - loss and regret and the past being much a part of his work, especially in the philosophical twilight his creation Gittes lives in. “To take the most dark and pessimistic view I can of life,” says Towne, “no matter how successful you are, as you age, you Iose more than you gained. And your awareness of the fact that it’s a losing game might even be highlighted by the fact that you are putatively at least, in an enviable position.”

“Sometimes to continue relationships,” Nicholson says of Gittes’s view of divorce and its consequences, “is less productive than to truncate them.” Like Jake Gittes, Jack Nicholson has grown up with a city, incarnated both what s glamorous and what’s tough about it - and most of us can hardly resist playing the game of identifying Jack with Jake. “They’ve said that about every character I’ve played,” says Nicholson. “All the way from the Devil on up. I guess that’s what you’re supposed to do, make them believe it’s you.”

The stumper question about him is not too different from the old saw: has (more and more) success spoiled Jack Nicholson? The due to the answer may be contained in a question Khan - the poker-faced Mulwray household servant who’s back from Chinatown—asks of Gittes at one point in The Two Jakes: “Does that mean you’re happy?”

“Oh, I don’t know,” answers Gittes, “Who can answer that one off the top of their head?” Khan’s response is thoroughly scrutable. “Anyone who’s happy.”

____________________________

Comments ()